Tiki Mania – Then & Now

Unlike Tiki himself, our story begins in the not-so-ancient past…

The first encounters between Tiki and modern man took place in the 19th century, as various artists, missionaries and escapists made their way to European outposts in Tahiti and French Polynesia.

The idyllic allure of Polynesia soon cast a spell of enchantment on its visitors.

The German philosopher Goethe captured it succinctly in 1828 when he yearned, “Oh to be born one of the South Sea Isles as a so-called savage, for once to enjoy human existence as pure and untainted by a fake aftertaste.”

He would be far from the last modern to burn with such longing for this Lost Eden…

Throughout the remaining decades, numerous Tiki artifacts and relics made their back to the motherland, where, in the early part of the 20th century, they served as creative muses to the budding surrealist and impressionist art movements.

Similarly, in America the annexation of Hawaii brought forth native music, floor shows, and décor into many mainland nightclubs during the 1920s.

The trend only intensified in the 1930s when Donn Beach and Trader Vic opened their own iconic Polynesian restaurants and nightclubs, giving Depression-era urbanites a firsthand look at and taste of strikingly exotic décor and nectars discovered in faraway lands.

Slowly but surely, Tiki culture was quickly making inroads into American culture. Yet it wasn’t until after WWII that the mania would break loose…

Two award-winning breakthroughs would help bring them into America’s consciousness like never before:

The first was Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl’s 1947 expedition from South America to Polynesia.

A zoologist and anthropologist, Heyerdahl was on an expedition in the Marquesas during the 30s, where he became convinced that Polynesians had migrated from the Americas, just as their flora and fauna seemingly did.

To prove his theory, he went to Peru and constructed the same kind of pre-Columbian balsa log raft once used by the Incans. Christening it Kon-Tiki after the Incan sun-god, Heyerdahl set sail in the Pacific with five crewmen, subsisting on a minimal diet of coconuts, sweet potatoes and fruits.

After 101 days and 4,300 miles, they finally reached the Tuamotu Islands.

Heyerdahl chronicled his exploits in 1948 with an immensely popular book The Kon-Tiki Expedition, and a movie of the voyage, Kon-Tiki, winning an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1951.

Tiki’s second breakthrough resulted from the close and extensive contact many American servicemen had with South Pacific cultures during the war. A romantic nostalgia for this Paradise Lost followed many of them back home.

One serviceman, James Michener, captured it in his immensely popular novel Tales of the South Pacific, winning the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Literature. The setting was the fictional “Bali Ha’i” where an American serviceman consummates his love with an exotic young beauty from the island.

The next year, Rodgers and Hammerstein brought sight and sound to it with their musical, South Pacific.

But musicals and books weren’t enough for a new American middle class yearning for escapism. They wanted to actively immerse themselves in faraway fun and adventure.

Let’s Go Native!

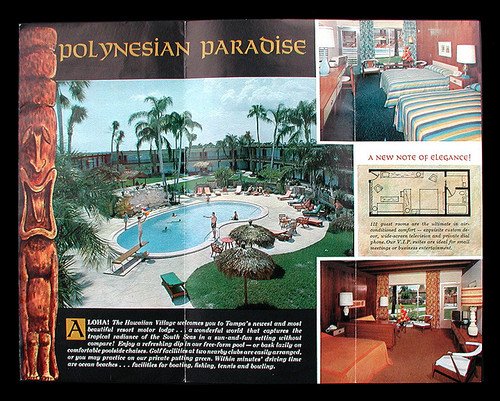

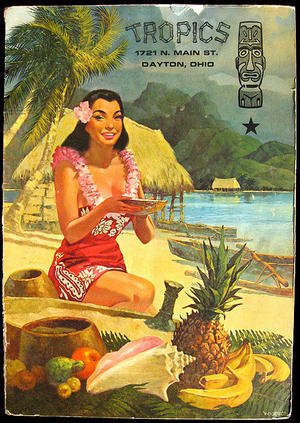

As a result, numerous Polynesian and Tiki-adorned restaurants, clubs, apartments, motels, golf courses and bowling alleys would spring up all across America like wildfire.

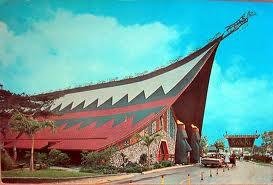

Whether it was the Kahiki in Ohio, the Tiki Cove in Alaska, the Islander in Boston or many others in between, A-framed Tiki Temples were an invitation for concrete-enclosed north Americans to step inside dimly-lit cocoons adorned with exotic foliage, tiki statues, bamboo, masks, torches, gurgling waterfalls and scantily-clad waitresses in island attire.

Along with the strangely colorful libations, floor shows, fire dancers and island music, the very best Tiki Temples provided an intoxicating sensory experience where the tie-choked “Organization Man” could whisk himself away, however briefly, to faraway and carefree lands.

The induction of Hawaii as America’s 50th state in 1959 only accelerated the mainland enthusiasm for all things Polynesia, spurring the hit detective show Hawaiian Eye and the huge popularity of Martin Denny’s Exotica album.

The stirring allure Polynesia had on America’s imagination wasn’t lost on the king of make-believe and wonder himself. A frequenter of Tiki Temples, Walt Disney founded his own Polynesian restaurant in 1962, the Tiki Terrace.

But the grip Tiki had on Disney’s imagination was just too bold…too feverish...

So the next year Disney created the Enchanted Tiki Room at his Disney Land theme park, with hundreds of animatronic birds and tiki gods singing, chanting and conversing all at once.

So the next year Disney created the Enchanted Tiki Room at his Disney Land theme park, with hundreds of animatronic birds and tiki gods singing, chanting and conversing all at once.

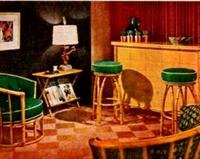

Many suburbanites decide to take the next step too, accenting their living rooms with Polynesian artifacts, tribal art and Island décor in a style that came to be known as Modern Primitive. Others went so far as to create Polynesian Edens right in their own backyards.

Before long, Americans began adorning their very own patios and pools with tikis, grass mats, bongos, palm leaves -- even building their very own Tiki bars. Finally, neighbors and coworkers could join together in tropical reverie without even leaving home.

Yes, it seemed that not only had Tiki conquered America’s eyes, ears, and stomachs, their very own sanctuaries were now his own.

Yes, it seemed that not only had Tiki conquered America’s eyes, ears, and stomachs, their very own sanctuaries were now his own.

But just as Tiki’s spell was at its strongest, other forces would knock him down from his throne…

Tiki’s Death – and Resurrection

In the late 1960s, just as Tiki had seemingly conquered the moderns, larger forces and events in American society would dethrone him.

Out of the cauldron of social unrest, war, recession, and a widening generation gap would emerge less vibrant tastes and fashions.

Faded puke-green, orange and brown hues replaced Technicolor saturation.

Molotov cocktails pushed aside Mai Tais.

Molotov cocktails pushed aside Mai Tais.

The emerging Baby Boomer generation viewed their parents’ whimsical and playful fascination with all-things Polynesia as tacky and diversionary ephemera.

It didn’t take long for Tiki’s new concrete empire to collapse. During the seventies, numerous Polynesian and Tiki-themed establishments across the land closed their doors. By the eighties, they were being torn down or heavily renovated.

Those that were left stood faded and in disrepair, their Tikis stolen, vandalized or hidden by overgrown foliage.

It seemed that, like so many other fashions before him, Tiki was destined to remain, at most, a minor historical curiosity.

It seemed that, like so many other fashions before him, Tiki was destined to remain, at most, a minor historical curiosity.

He would have remained as such – except for the tenacity of a few dedicated “Tikiologists” committed to restoring Tiki to his rightful place in popular American culture.

By the 90s irony and kitsch had beed rediscovered, and the newly emerging internet could now bring together Tikiphiles together for the first time.

In 1995, Otto von Stroheim launched the Tiki News zine to chronicle his adventures in discovering Tiki artists and artifacts, networking a growing community of enthusiasts.

The next year, he co-curated “20th Century Tiki” in Los Angeles, the very first Tiki art exhibit ever -- and spawning many others.

Even more extravagantly, in 2001 von Stroheim launched Tiki Oasis, by far the largest and longest running Tiki Event on the planet.

Each summer in southern California, hundreds of Tiki enthusiasts, artists and musicians get from around the world gather at historic Tiki landmarks for a few days to celebrate and honor Tiki culture in retro-kitsch reverie.

From a more academic vantage, Tikiologist Sven Kirsten began documenting numerous and long-forgotten anecdotes, landmarks, legends, pictures, artifacts, and personalities from America’s Tiki era in The Book of Tiki and Tiki Modern.

Even more significantly, major record labels began reissuing albums from Exotica artists such as Martin Denny, Les Baxter, Arthur Lyman and Yma Sumac.

Similarly, Capitol Records dug within their vaults for (often obscure) Exotica and Polynesia-themed music as part of their Ultra-Lounge compilations.

But probably the most heartening indicator of Tiki’s final triumph and permanence within popular culture are the dozens of new Tiki bars and restaurants that have emerged all around the world since the beginning of the 21st century.

From the Islander in Pittsburgh… the Tiki Room in Stockholm…to the Tabou Room in Berlin and many, many others, Tiki’s renaissance is a world-wide one.

And this time, he’s here to stay.